“PEACE” FOR OIL?

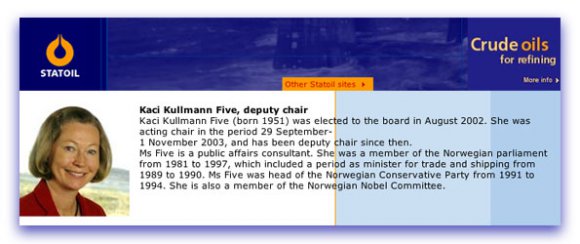

Prior to her position on the Nobel Committee, Kullmann Five served as deputy chairman of the board of Statoil, Norway’s largest oil company, from 2003-2007

Kaci Kullmann, con intereses petroleros en Colombia, dirigió la entrega del Nobel a Santos

“Peace” for Oil?

Prior to her position on the Nobel Committee, Kullmann Five served as deputy chairman of the board of Statoil, Norway’s largest oil company, from 2003-2007. The Norwegian government, which played a key role in the negotiations as one of two guarantors, is the majority share-holder in Statoil. And in 2014, under the government of Juan Manuel Santos, Statoil was awarded a license for off-shore oil exploration in the Caribbean Sea, marking its entry into the Colombian oil market.

By Lia Fowler*

October 8. 2016

@lia_fowler

When the leader of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Kaci Kullmann Five, announced the decision to award the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize to Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos on October 6, observers around the world were stunned. Italy’s Corriere della Sera’s headline questioned whether the choice made sense; Spain’s El Mundo called it inappropriate; and the Wall Street Journal labeled it strange. After all, Santos was awarded the prize for his participation in a 6-year peace process with Colombian narco-terrorist group FARC, that was rejected by the Colombian people. In a plebiscite on Oct. 2, only 17 percent of the electorate endorsed it. Kullmann Five argued that the prize was awarded to honor the work that had been done – with Norway serving as a guarantor — and encourage further peace efforts. But the real reason for the bizarre decision might be found, as has been true of many of the foreign countries involved in Colombia’s dubious peace process, in economic interests – specifically, oil.

Prior to her position on the Nobel Committee, Kullmann Five served as deputy chairman of the board of Statoil, Norway’s largest oil company, from 2003-2007. The Norwegian government, which played a key role in the negotiations as one of two guarantors, is the majority share-holder in Statoil. And in 2014, under the government of Juan Manuel Santos, Statoil was awarded a license for off-shore oil exploration in the Caribbean Sea, marking its entry into the Colombian oil market.

It is not surprising anymore to find that the people and countries vested in the peace deal are linked to oil companies with significant interest in Colombia and dependant on the Santos government’s oil licenses and concessions. In a March 12, 2016 article, I reported on the conflict of interest of Bernard Aronson, U.S. Envoy to the talks held in Havana. Aronson is the founder and managing partner of Acon Investments, a private equity firm that has a controlling interest in Vetra Energia. Vetra’s investment in Colombia is the result of government concessions awarded in 2010 and 2012. (1)

In an August 2, 2016, article, I reported on the bizarre role Switzerland played in the peace talks, by accepting the inked deal between Santos and the FARC for deposit in its Federal Council – a premature move, as the document was rejected by voters. Switzerland’s role also seems motivated by economic interest in oil, as Swiss-based commodities trading companies – which generate four percent of Switzerland’s GDP – have invested billions of dollars in Colombia’s oil and coal industries, thanks to concessions from Santos’ government.

As to Norway’s interests, despite its reputation for being among the least corrupt nations in the world, state-controlled Statoil does not enjoy that distinction. In

2004, Statoil was found guilty of corruption by a Norwegian court for bribing Iranian political figures in order to obtain oil contracts. In 2006, the company settled a case with U.S. authorities related to the same incident, paying a fine of USD $21 million and admitting to bribing Iranian public servants to secure contracts and obtain confidential information.

Following the scandal, Britain daily The Telegraph quoted Kullmann Five – who was the spokesman for the Board of Directors – as saying the company planned to continue its international activities “with undiminished vigor.” Indeed, it did.

When the former Statoil board member turned Nobel Committee leader announced the awarding of the Nobel prize to Santos, a puzzled public speculated as to its motivations. Certainly, it was not for Santos’ great contribution to peace – having spent six years and billions of pesos on a failed project. Some speculated that the Committee wanted to reward Norway’s own efforts in the peace process. But Kullmann Five’s association with the state-controlled oil company and its recent drilling concessions from Colombia suggest a more material motivation. And while there is no evidence of bribery in this case, it could be one more example of the quid-pro-quo racket of “peace.”

*Lia Fowler is an American journalist and former FBI Special Agent.

____________________________

(1) BERNARD ARONSON: THE CONFLICTING INTERESTS OF “OUR MAN IN HAVANA’ http://www.

(2) SWITZERLAND’S BUSINESS INTERESTS IN COLOMBIA’S FALSE PEACE http://www.

Comentarios

3 pensamientos sobre ““PEACE” FOR OIL?”