IN HONOR OF GEN. HAROLD BEDOYA AND HIS MISSION

Bedoya depicted vividly for his American audience the horrors which Grasso’s narcoterrorist allies had brought, such as some 4,000 children, age 10-16, kidnapped from their families to become cannon fodder for the FARC forces, and the estimated 1,500 adult Colombians kidnapped and held in FARC camps

In Honor of Gen. Harold Bedoya and His Mission

Bedoya depicted vividly for his American audience the horrors which Grasso’s narcoterrorist allies had brought, such as some 4,000 children, age 10-16, kidnapped from their families to become cannon fodder for the FARC forces, and the estimated 1,500 adult Colombians kidnapped and held in FARC camps

By Gretchen and Dennis Small

By Gretchen and Dennis Small

May 29, 2017

http://larouchepub.com/spanish/other_articles/2017/0516-bedoya/bedoya.html

Colombian patriot Gen. Harold Bedoya passed away on May 2 at the age of 78, after a battle with cancer. In his distinguished career, he had served as Commander of Colombia’s Army and Armed Forces, as Defense Minister, ran twice for president, and fought to rally his fellow citizens to drive the drug trade and all its instruments out of his beloved Colombia until the very end of his life. Bedoya always saw himself, as he said, as being “on active duty to the nation.” And he did so knowing that he was acting on behalf of humanity as a whole.

Informed of Bedoya’s passing, American statesman Lyndon LaRouche asked that his name be added to those remembering Gen. Bedoya with respect and appreciation, “for my loyalty to that mission which he represented.”

In February 2003, LaRouche and Gen. Bedoya held a joint seminar in Washington, D.C., on the subject of “The War on Drugs and the Defense of the Sovereign Nation-State.” In their remarks, both addressed the quality of leadership required to pull the world out of crisis. “The issue here, that General Bedoya is most actively representing, is a crucial one for us all,” LaRouche told the gathering. “The drug-pushing operation is the enemy of humanity…. Kill it, and save the people. And wherever we find someone in a nation, who is capable and willing to stand up and defend those principles, we must work with them. We must find them as representative of what we hope to build on this planet, a community of principle among sovereign nation-states, as the future … permanent guarantor of a condition of peace on this planet, from which standpoint humanity can go forward, to become finally, what we have not yet achieved: to become truly the human beings we were made to be.”

Bedoya, for his part, stated that “the crises that we are facing today throughout the world, but most especially here in the Americas, require leaders, great leaders, who understand the issues, and who are willing to assume responsibility, and fight, come what may, without becoming intimidated by lies and slanders, by tragedies, by lack of means or resources. Because, above and beyond man lies the strength of a God, Who shall lead us to the promised land of freedom, democracy, and all of that for which we have been born, and for which we shall die.

“So, I’m not too concerned about living through moments of difficulty,” Bedoya continued, because it is precisely at such moments of crisis that people are reborn, solutions emerge, and leaders such as Lyndon LaRouche appear, to tell the world to wake up, to tell Americans to please not be indifferent to this tragedy that we are facing throughout the Americas and the world.”

Gen. Harold Bedoya was just such a leader among men. At a time when most around him, in Colombia and across the Americas, were taking the easy way out and succumbing to the devastating paradigm shift that increasingly tolerated legalized drug consumption and production, Bedoya took personal responsibility to free Colombia from the murderous narcoterrorism which the Colombian people have suffered for decades, whether that terror came from the Medellin or Cali cartels or from the FARC cartel today. He stood up against every Colombian government which capitulated to the “lead or money” terror –accept our bribery or be killed—waged against the nation by the Wall Street and the City of London financial powers which deploy the drug cartels.

Bedoya said “no.” He refused to accept that Colombia cut a deal with the drug trade, and become a narco-state. Not when Presidents Ernesto Samper Pizano (1994-1998) and Andrés Pastrana (1998-2002) handed enormous swaths of territory (and the Colombians within that territory) over to the FARC cocaine cartel terrorists; and not when today’s British project, President Juan Manuel Santos, sought to co-govern with the FARC and legalize the production, trafficking, and consumption of narcotics first in Colombia, and then worldwide.

Bedoya’s unbending opposition to any “peace” with the drug trade was premised on moral grounds; he understood the drug trade to be “a crime against humanity.” In an interview with Executive Intelligence Review in 1998, Bedoya called the idea of legalizing drugs “absurd.”

“We have to fight the drug-trafficking mafias, so that not only will they not continue to produce drugs, but so that they cannot continue to cause the horrendous damage to which the youth and the entire world are being subjected through drugs…. I believe that what we have to do here, rather than legalize drugs —it makes no ethical sense to do this— is to make drug-trafficking a crime against humanity, and we should try the drug mafias in international courts, as befits any civilized society in the world.”

When President Samper Pizano forced Gen. Bedoya into retirement in July 1997 as demanded by the FARC and its ELN guerrilla cousins, Bedoya did not waste a moment. Within a month, he was organizing a campaign for President based on a new political movement, Fuerza Colombia¸ which he mobilized on the principle that Colombia had a right to develop and prosper, free of drugs and narcoterrorism. As he campaigned across the nation (which he knew like the back of his hand from his travels to nearly every corner and village during years of active military service), he told his fellow Colombians: “Don’t try to sell me the story, that in order to achieve peace, we have to hand over pieces of our country to criminals, to terrorists… All is not lost.”

An International Ambassador to Save Colombia. Knowing that “what we military men call the `theater of operations’ of the mafia and the drug trade, is worldwide,” Bedoya took his campaign against the drug menace to the rest of the Americas. Colombia did not have the resources to win a war against the international drug trade alone. Over the next few years, he traveled to the United States, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Peru organizing for these, and other nations “to forge an alliance to do battle against the drug trade.” Each nation involved must commit to crushing the facet of the drug trade which afflicts it, be it crops, precursor chemicals, money, transport, weapons supply, or consumption, he said.

He argued that with such an alliance, the drug trade could be wiped out in two years—provided it was accompanied by economic development. Colombia has been reduced to ashes economically by the drug trade, “narcotized,” no longer producing its own food, Bedoya said. He proposed a “Marshall Plan” approach in which the great world powers would collaborate in the reconstruction of Colombia. With international contributions of capital, technology, and trade —and without International Monetary Fund conditionalities, he insisted— Colombia could establish development poles in the regions devastated by the drug trade, in which the State would initiate a civil-military mobilization, and deploy its military engineers to help build schools and large infrastructure projects: highways, bridges, railways, airports, canals, sea and river ports, thus “putting the land to work once again to grow food instead of drugs, recovering the jungle that was burned or slashed to produce coca.”

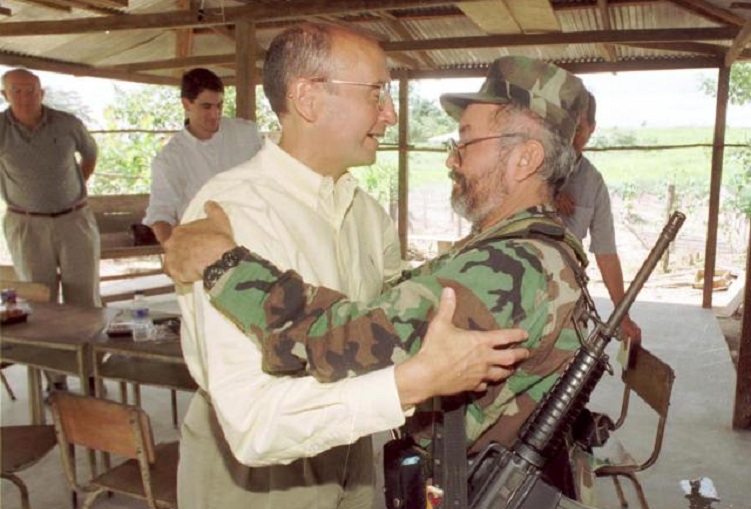

Turning the Tide in the United States. Everywhere he went, Bedoya fearlessly took on Wall Street and the U.S. State Department, by name, for backing the drug mafias. In June 1999, Madelaine Albright’s State Department had organized the visit of the head of the New York Stock Exchange, Richard Grasso, to the FARC-controlled Caguán demilitarized zone. Upon his return, Grasso announced on a conference call with the press, that in his view the FARC understood capital markets very well, and he hoped that, soon, he could escort “Comandante Tirofijo” –the head of the FARC cocaine cartel—down the hallways of the NY Stock Exchange to discuss “mutual investments.” That same month, the IMF publicly ordered the Colombian government to include drug “production” figures in its GDP calculations, treating drugs as just another input into the Colombian economy.

In early September 1999, Gen. Bedoya made an intervention in Washington, D.C. which proved decisive. The Wall Street faction in the State Department was pressing hard for Colombia to consummate the deal with the FARC signaled by the Grasso visit. Anti-Drug Czar Gen. Barry McCaffrey and other patriots, in and out of government, opposed that immoral policy as leading to a strategic disaster.

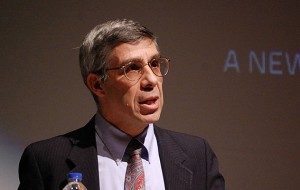

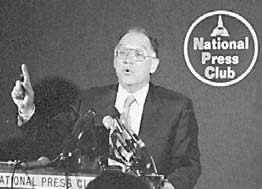

Gen. Bedoya came to Washington in the middle of this fight, on a trip organized by LaRouche’s EIR magazine. For seven days, from 7 a.m. to midnight, Bedoya held private meetings with more than a dozen Congressional and Senate offices, including nine Representatives and three Senators personally; with high-level officials at the State Department; and with U.S. military officers, urging the United States to join Colombia in a total battle against narcoterrorism and the drug-trade. He addressed a special EIR seminar organized for diplomats from around the world; gave numerous press interviews, including a very-well attended briefing at the National Press Club; addressed 1,000 American citizens from across the U.S. at the semi-annual Schiller Institute conference; and he spoke to a meeting with the Colombian community.

In every speech, seminar or personal meeting he had, as he had in his earlier travels in South America, Bedoya held up or spoke about the famous “Grasso Abrazo” picture of Stock Exchange head Grasso hugging Comandante Raul Reyes, the head of FARC finances, during his visit to the Caguán. Bedoya asked, as he had in every stop in his prior tour in South America: What is Colombia supposed to conclude from such a visit? “It would be very good if the government of the United States were to interrogate those gentlemen, who landed on the same airstrips from which the drugs which so concern U.S. authorities are exported.”

Bedoya depicted vividly for his American audience the horrors which Grasso’s narcoterrorist allies had brought, such as some 4,000 children, age 10-16, kidnapped from their families to become cannon fodder for the FARC forces, and the estimated 1,500 adult Colombians kidnapped and held in FARC camps His detailed map briefings made clear the strategic implications of just how much of Colombia’s territory was already in the hands of the narcoterrorists.

Bedoya called upon the United States to understand that Colombia’s fight is its fight, and to find the political will to support Colombia and its neighbors in an all-out political-military war against narcoterrorism, and to provide the kind of economic development needed for victory. His message was simple: “This is not a Colombian mafia; it’s an international mafia. United, we can finish them off.”

He specified that the assistance Colombia needed: modern military weaponry and equipment, with training for their efficient use, satellite and other intelligence; and

Marshall Plan-style economic aid for reconstruction. Under no circumstances, he insisted, does that mean foreign troops entering Colombian territory, repeating to everyone on this point: “no, no, no, no.”

Bedoya laid out his message for the record in an interview with the United States Information Agency’s Foro Interamericano [Inter-American Forum] television program, a message which is as urgent today as it was then:

“The U.S. doesn’t have to send troops to Colombia. Providing technical and logistical aid is the most important, and don’t send out signals that coca is good, as one Wall Street faction did—Mr. Richard Grasso practically walked into the laboratories to negotiate with Wall Street’s money. No one can fathom what Wall Street and the International Monetary Fund are doing, demanding that Colombia include drug trade revenues as part of GDP! That makes us a narco-democracy, in which drugs here, and in the world, are practically being legalized….

“If the United States doesn’t do what it should do, it will suffer the consequences…. So the United States must make a decision very soon. Every minute, every day, every second that passes, means that the problem will be solved with more [drug] money, more deaths, more terrorism, and, of course, more drug-trafficking….

“The peace process exists because the U.S. government backs it. That is, the U.S. has that responsibility, and that’s why it’s so important that the United States rectify and correct its mistake…. Colombia is dying…. A rectification in time could save Colombia and America.”

Several years later, qualified U.S. military sources told EIR that Gen. Bedoya’s trip had tipped the balance in the fight in Washington against Wall Street’s legalization-through-“peace” faction. The decision was made to aid Colombia through Plan Colombia instead. Plan Colombia did not meet the criteria required for victory which Bedoya had specified, but it did establish the principle that the U.S. must support Colombia in its fight against drugs and narcoterrorists. The basis was laid for the collaboration, albeit more limited than that required, which was critical to Colombia’s military campaign under President Alvaro Uribe Velez (2002-2010) which freed major sections of Colombia’s territory and people from the FARC cartel’s control, lowering drug production significantly in the process.

A People’s General. As a true military leader, Bedoya understood that “wars without a valid moral purpose are a total failure. The fundamental thing,” he argued, “is to determine if there exists a higher-order moral purpose that justifies the war, and also if there is the will to win and to impose a just, and therefore lasting peace.” He went directly to the Colombian people because he understood that “wars are not won by powers; wars are won by the people. The only ones capable of resolving an internal problem are the people themselves.”

His entire life, Gen. Harold Bedoya stood his ground against the deadly tide of the international drug trade, and sought to bring about a peace fit for human beings. For that, the nation of Colombia, and an entire generation of American youth owe him a debt of gratitude.

___________________________________

Notes:

[1] “Combatir al narcotráfico es defender la soberanía”, discurso de Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XVII, núm. 4-5, 2ª quincena de febrero y 1ª de marzo de 2000.

[2] “El `Plan Colombia’ de Pastrana, contubernio con el crimen organizado”, discurso del general Harold Bedoya. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XVII, núm. 4-5, 2ª quincena de febrero y 1ª de marzo de 2000.

[3] “A acabar con el narcoterrorismo: Gral. Bedoya en entrevista con EIR”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XV, núm. 13, 1ª quincena de julio de 1998.

[4] “General Bedoya: Para ganar, hay que movilizar a la nación”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XV, núm. 9, 1ª quincena de mayo de 1998.

[5] “General Bedoya: en dos años se puede erradicar al narcotráfico”, discurso del general Harold Bedoya Pizarro en el seminario de la EIR en Bogotá, Colombia, titulado “El proceso de paz en Perú y en Colombia”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XV, núm. 16, 2ª quincena de agosto de 1998.

[6] “Colombia sufre una agresión del narcoterrorismo internacional: discurso del general Bedoya en CARI”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XVI, núm. 17, 1ª quincena de septiembre de 1999.

[7] Ibíd. Vea también “General Bedoya: en dos años se puede erradicar al narcotráfico”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XV, núm. 16, 2ª quincena de agosto de 1998.

[8] “Alianza continental contra el narcoterrorismo, propone el general Bedoya en Argentina y Uruguay”. Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XVI, núm. 17, 1ª quincena de septiembre de 1999.

[9] “El general Bedoya propone guerra al narcoterrorismo: `Todos unidos los podemos acabar’,” entrevista con el programa de televisión “Foro Interamericano”, de la Agencia de Información de los Estados Unidos (USIA). Resumen ejecutivo de EIR, Vol. XVI, núm. 19, 1ª quincena de octubre de 1999.

[10] Ibíd.

[11] “La nueva OTAN y el Plan Marshall para Colombia por el general (r) Harold Bedoya Pizarro”, discurso del general Bedoya en el seminario de la EI

Comentarios